MoSCoW, Velocity, and the Work That Actually Matters

There’s a particular kind of stress that comes from feeling productive every day, yet watching the important thing stay unfinished.

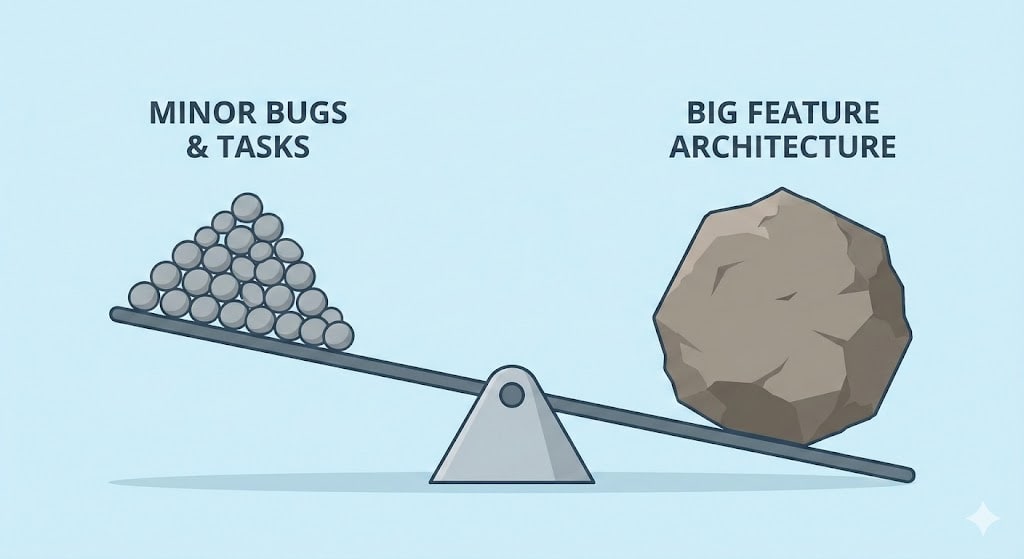

I’ve felt it most when I’m sitting on a backlog that looks “manageable” in the small: lots of minor bugs, tidy refactors, quick optimisations. The kind of work that gives you clean standup updates and a satisfying “Done” column.

And then there’s the other kind of work. The slow, architectural kind. The one that doesn’t move in neat increments, but quietly determines whether the next feature launch will be smooth or painful.

This post is about a trap I keep falling into: optimising for visible velocity instead of delivered value.

And why the MoSCoW method, useful as it is, often isn’t enough on its own when you’re trying to prioritise engineering work inside a team.

MoSCoW (Must, Should, Could, Won’t) is clean, intuitive, and easy to explain.

The problem is that when you apply it to internal engineering backlogs, it can become a mirror for anxiety instead of a tool for trade-offs.

Where MoSCoW breaks (for me)

On paper, “Must” is supposed to mean “we do not ship without this.”

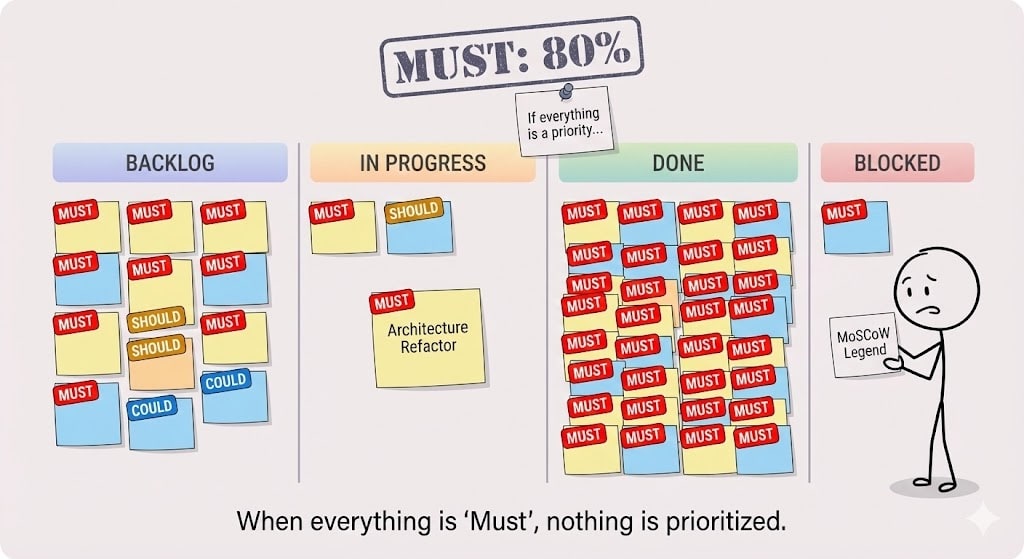

In reality, I’ve watched “Must” absorb everything:

- A feature needed for a launch becomes a Must.

- A reliability issue that hurts a non-trivial slice of users becomes a Must.

- A demo-prep request from leadership becomes a Must (even if nobody calls it that out loud).

- A piece of tech debt that keeps biting you becomes a Must, because you’re tired of being afraid of it.

At that point, MoSCoW is still describing something true, but it’s no longer helping you decide.

If 70-80% of the backlog is “Must,” then “Must” doesn’t mean priority. It just means “this makes me nervous.”

And MoSCoW doesn’t force you to answer the question that actually matters in a week with limited time:

What will we not do, on purpose, so the right thing ships?

A better question than “Is it a must?”

Eventually, the framing that helped me wasn’t “Must vs Should.”

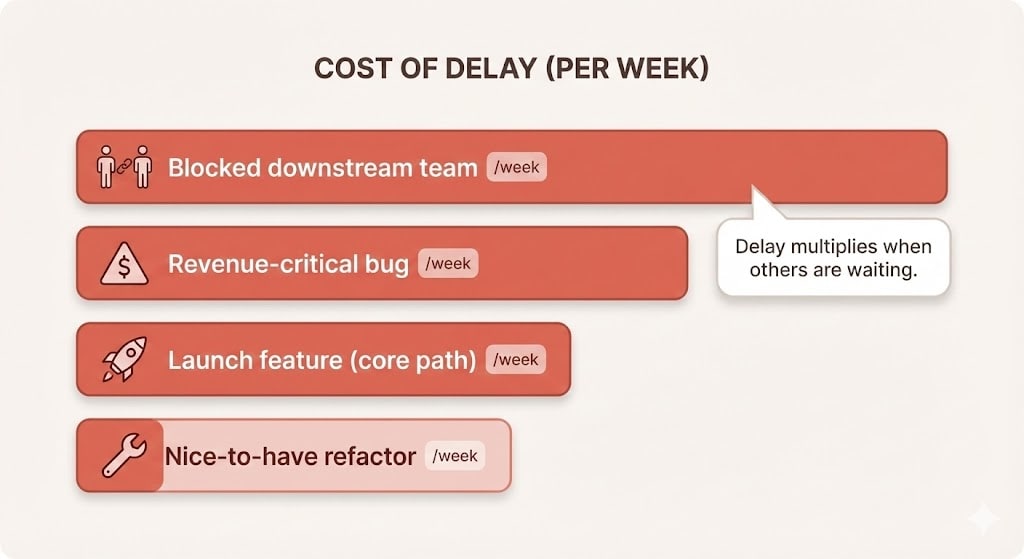

It was cost of delay:

What is the economic cost per week of not having this done?

Sometimes that cost is direct revenue. Sometimes it’s churn risk.

But in engineering, the cost of delay is often hidden inside other people’s time.

If my work blocks another developer, then my “small delay” isn’t small. It’s multiplied by the burn rate of a whole second workstream.

That’s the moment where “five quick tickets” stops looking productive.

The system isn’t asking, “How many tickets did you close?”

It’s asking, “Did you remove the bottleneck?”

The framework that actually changed my week

I still like MoSCoW. I just don’t rely on it alone.

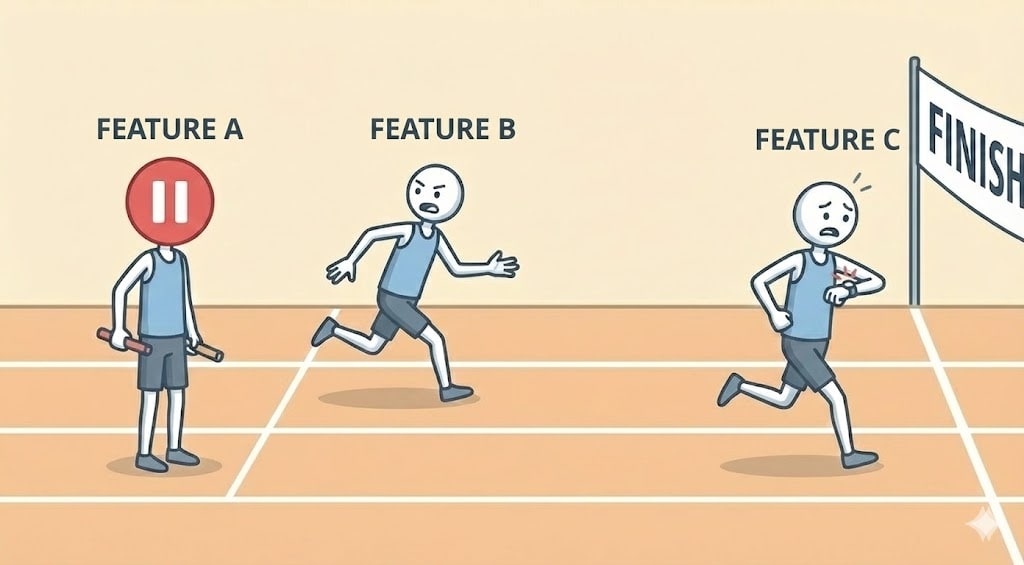

The shift for me was moving from “clear the board” thinking to sprint goal thinking.

Instead of chasing ticket volume, I try to align with one outcome that must be true by Friday.

Old mindset: “Close 15 tickets.”

New mindset: “Enable X capability end-to-end.” (So another person/team can move.)

Once the goal is clear, prioritisation becomes brutally simple:

Does this task directly move the sprint goal forward?

If yes, it earns protected time.

If no, it needs a strong reason to interrupt the thing that matters.

This is where MoSCoW becomes useful again, but in a different role.

Not as the decision-maker.

As the language you use to negotiate scope after the goal is set.

The part that feels uncomfortable (but matters)

Optimising for goals instead of tickets has a social cost.

It means there will be days where your standup update sounds boring.

It means you’ll say “no” to things that are genuinely important, just not important right now.

It means you’ll ship a big piece of value while leaving a trail of small annoyances behind you, and you won’t get the dopamine hit of seeing ten green checkmarks.

But the trade-off is that the right thing moves.

And in my experience, that’s the difference between feeling busy and being effective.

A simple way I think about MoSCoW now

If you want a lightweight way to combine the clarity of MoSCoW with the decisiveness of goal-based prioritisation, here’s what’s worked for me:

If you only remember one thing: let the sprint goal constrain “Must.”

- Pick one sprint goal that leadership and engineers agree is the bottleneck.

- Define Must as “without this, the sprint goal fails.”

- Define Should/Could as “nice, but not at the expense of the sprint goal.”

- Define Won’t as a real commitment (for this sprint), not a vague “later.”

The key is that “Must” is constrained by the goal.

Not by your fear.

Closing thought

I don’t think prioritisation is something you solve once with a clever acronym.

It’s a daily practice of protecting deep work, making trade-offs explicit, and remembering that the backlog will always be infinite.

If you’re using MoSCoW and everything is turning into “Must,” it might not mean you’re bad at prioritising.

It might mean you’re trying to use a labeling system to do the job of a strategy.

What’s one thing you could define as your “sprint goal” this week, so that on Friday, you can point to an outcome instead of a ticket count?